A’AGA Something to be told: On O’otham Farming

April 11, 2017

By Billy Allen

Spring has sprung and winter’s rainfall has turned our jeved green. A lot of plants are blooming, but many are not yet producing food. How did our O’odham and Piipaash peoples survive?

Coaxing food from the desert was not easy. It was hard physical labor but the O’odham and Piipaash farmer was up before the sun rose, worked until noon, rested until mid-afternoon and then worked until dark.

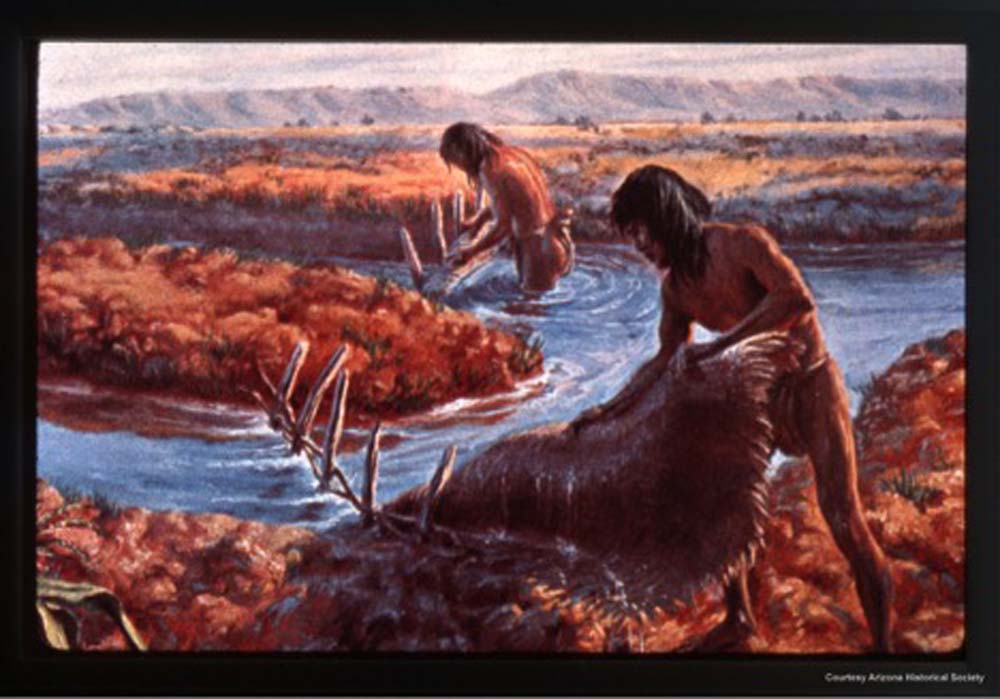

He worked slow and steady to prepare fields, clear canals, and rebuild brush dams -all while under the threat of O:b or enemy attack. A good food harvest was the reward and maybe a new field for new cleared land usually went to males who showed to be s-vagima or hard workers.

Old Hohokam canals were used, but new canals were also dug. These canals were dug with sticks and a crude wooden shovel. Our ancestors survived on what they raised, stored, gathered or hunted, so laziness was not tolerated.

At this time of the year, the “savings account” of last summer and fall -- peas, tepary beans, maize and squash were almost gone. Once I heard a modern Hohokam descendant utter, “Don’t plant something pretty, plant something I can eat!” O’otham and Piipaash can tolerate many things, but not hunger pangs.

Since March was Kui I’vakidag or when mesquite leaves bloom, the Akimel and Piipaash farmer watched the mesquite and when the leaves came out; this was the signal to plant maize, beans and cotton. A second crop would be planted in late July to take advantage of the summer thunderstorms. This second growing season ended with the first frost.

When not doing community field work, hunters ventured from the village. But there was no guarantee anyone leaving the village would return safely. Because we owned the best farmland in this area, we had to fight constantly to keep it.

Our keli akimel or old man river flowed down from the eastern mountains making the water heavy with alkali. To combat this, keli akimel farmers would flood fields to wash away the alkali. Individual families would prepare an oidag or field near a canal. A fence of willow or mesquite branches surrounded the oidag.

Sometimes the willow and mesquite brush piled up to keep out small animals, took root and became a living fence. On nearby hills small plots were cleared to take advantage of the runoff from the rain. On these stair-like plots agave and yucca were planted.

By doing this, it cut down on the distance they had to walk to gather these foods, not to mention being safer. In the Vahki or Casa Blanca area the biggest and most productive fields were on sandy islands in the middle of the keli akimel.

When the Spanish introduced pilkan or wheat, it quickly became a staple because it could be stored in large baskets to protect against starvation. Initially when the pilkan was harvested, women beat the wheat stalks with sticks to separate the grain. Then the grain was winnowed -- gently tossed in the air so the hevel or wind could blow away the chaff.

At this time of the year, the Tohono O’odham, would journey down to our jeved to help with the harvest. It was also an opportunity to strengthen ties between the tribes with new courtships.

In 1775, when a Spanish military post was moved to Tucson, Akimel and Piipaash farmers supplied much of the pilkan. By 1870, O’odham and Piipaash wheat production had reached 3 million pounds.

To keep up with the volume, horses were walked over the crop to separate the grain. Wheat could be traded or sold to Americans. Flour mills were built at Vahki or Casa Blanca and Sacaton. Today wheat remains a cash crop on our jeved.

Many hardships had to be dealt with in raising a good crop. Our ancestors raised food to eat; today we raise food to buy food. Coaxing food from the desert was a way of life for our ancestors; it was not easy for starvation was always on the minds of tribal elders. Ancient farmers lived with nature and respected nature. I want to think we still do.

Information was taken from Akimult Aw A Tham; The River People by Guy Acuff, The Pima-Maricopa by H. Dobyns and Peoples of the Middle Gila by John P. Wilson. Photo is courtesy of the Arizona Historical Society.